| Chapter 4: |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Summer of Love ( I wasn't in San Francisco; I was in Illinois designing motorcycle stuff) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| June 3 through September 12, 1969 Craig redesigns the Rocket 3 Black writing, Don Brown, Blue Craig Vetter | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

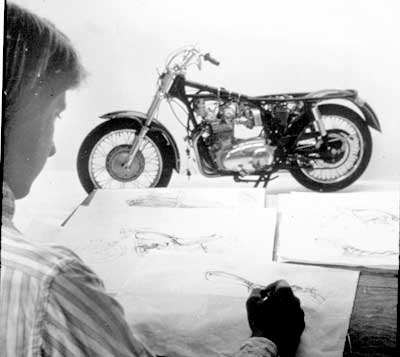

| Craig recalls: I had previously sent a Series 1600 Vetter Fairing to BSA for evaluation so I quickly put it on. The ride to Illinois was a great time to get to know the Rocket 3. I loved the engine and the sound of the BSA triple, but not much else. Riding it was like sitting on an ugly board. In 1000 miles, I pretty much knew what had to be done. Much of the story appears in "A Hurricane Named Vetter," so I will not repeat it here. This then, is my story from a perspective 35 years later.” | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

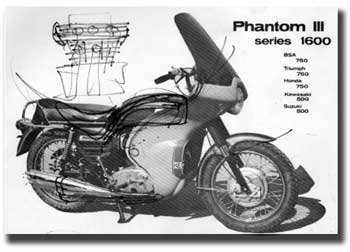

| This is what the BSA Rocket looked like when I drove it to Illinois. I sketch on anything around me. This is doodling on one of my Vetter Fairing brochure pages. I love design and I love motorcycles. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Let me first state that I design for motorcycles because motorcycles do more with less energy. Motorcycles got 40mpg while cars got 15. Virtually everything that I think is worth doing must first do more with less. The biggest reason for doing more with less is to make our resources last longer. The second is to reduce our purchase of foreign fuel which makes any country vulnerable. I want to be part of the solution, not part of the problem. I'm sure you understand. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "The designer of a motorcycle for Americans should be an American motorcyclist." You can quote me. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| People from different cultures and of different ages have different tastes. As similar as the English and Americans are, in 1969 we rode differently. They liked flat bars and rear sets. We preferred sitting up with wide bars. I have always designed for me. Not you. Me. When Don Brown called me in 1969, I was a 27, unmarried, and loved design and motorcycles. I understand my generation. Don could not have called a better person to design a motorcycle for Americans my age. Don made things easier when he asked for a slim, 1 1/2 person design. Somehow, motorcycles look better that way, but they may seem not as practical unless you understand how form follows function the way I do. For me, the function of the Hurricane was to make me stand out in a world of foreign motorcycles. The function of my design was to look American. Its function was also to make its rider be noticed by women. Further, I wanted my design to withstand the test of time. Something that looks new and exciting today will look old and tired tomorrow. My work must be classic and enduring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Hurricane in the British National Motorcycle Museum, Birmingham, in the summer of 2003. The place burned down two weeks later. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Museums should want to show it in 50 years. Its function was also to improve the financial position of BSA and the state of motorcycling in general. The function of my design then, was to say "Look at me because I am special." The function of the Vetter Rocket was to make me get noticed for the right reasons. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I already liked the looks of the triple engine but somebody had emasculated it by shaving its cylinder head fins off. I put them back on. I also put as much space around it as possible, sort of like framing it with the bodywork as a prized painting would be, to make it the center of attention. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I am the first of the "Plastic Generation" of designers. We plastic designers are able to see more free flowing shapes as possible and are not as restricted in our thinking as, say, metal-stamp designers. Plastics salesmen had no objections from me. They did not have to show me why plastic was better than metal. I already knew it. So you can see that I had no fear in making a one piece seat and tank. Computer Assisted Design (CAD) is great today, and I use it. But nothing beats sitting on your design, feeling it between your legs, holding the handlebars and making 'Rumm Rumm' sounds. I do a lot of that when I design a motorcycle. Sit on a Hurricane or a Mystery Ship and you will feel the result. I wanted my design to be producible so I made no changes that I thought might jeopardize its production. It also was to incorporate a new Ceriani - style front end. Don sent me a set of Cerianis saying that it pretty much represented the English version coming soon. The problem was that he sent me short, road racing forks and I had to machine slugs to bring the bike back up level. And that seems to have led the English to believe that I had extended the forks, so they extended their Ceriani copies, too. The fact is the Vetter Rocket that I made had stock Rocket 3 length forks. The exhaust system was a nightmare. I don’t like arranging three pipes. Don, as I recall, said do whatever you want with the pipes and the engineers will make them work. The best I could come up with was the now famous, fanned out configuration that actually employed the real megaphones that Jim Rice had used on his BSA flat Tracker. The engineers would make them work as mufflers. Apparently, they did make them work, but only good enough for any motorcycle made through December of 1972. After that, they would not meet federal noise emission standards. This is probably one of the reasons that the Hurricane was produced only for that one year. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don really wanted the bike to be yellow, and if you scraped the paint from the Vetter Rocket, you’d find that it was once yellow . . . for about ten minutes. I could not stand it. I think this was the point when Don gave up on directing me and finally realized that I was going to produce something good for him. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

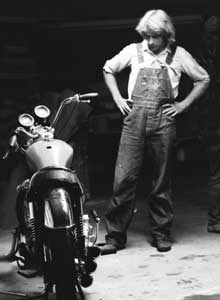

| 1969 me & the BSA with the ugly stuff removed. Well, I never really liked the pipes. If you notice, most of the photos I took of the Vetter Rocket in 1969 were of the left side… not from the pipe side. But I was wrong. The pipes helped make the Hurricane famous! Somebody once said, "The three pipes make the bike look loud." He was right! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don and Craig learn to work together | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don continues: Preparing for the Fall Dealer meeting in 1969 made this a very busy time for me, but the styling project being done by Craig was still in my mind. When Craig sent his reports, I would take pen in hand and send him my thoughts about what had been done so far. There were several things I didn’t like initially, and I made my views known to Craig. We argued politely by telephone and by mail.” | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Then, one day Craig’s report contained a Polaroid of what became the essence of his new design: the famous one-piece seat and tank, which was an entirely original concept. The picture only showed a mockup. It was not a finished product by any stretch. but when I saw it I realized that Craig was on to something of importance, and from that point on I backed away from micro-managing the project. To Craig’s credit, he hadn’t let my ‘barbs’ get in his way. He would answer each critique with an explanation of why I was wrong or whatever. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I think Don was impressed because I combed my hair | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Craig says: When the bike was finished and I had sent the final Polaroid to Don, he knew he was beaten. "It’s not my bag," he wrote, "but that’s probably good." I had earned Don’s trust. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Finished Vetter Rocket 3, Sept. 12, 1969 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don to Craig: I think I was referring to the long forks, or something else. I liked the seat/tank design from the first time I saw it. Don recalls: By the end of that year I had had enough of Peter Thornton and his whole deal. I didn’t like him or his associates who were acting as “consultants”. I told my wife, Teri, that I intended to resign as soon as I had informed the chairman. I said nothing to Thornton about my intentions. Rumors about the Rocket 3 design project had gotten to Thornton, and he called me into his office. "What’s this about a secret project?" he asked. "Oh that," I responded, then I had my secretary take all of my files on the project to Thornton. He ordered me to arrange for him to see the bike. I called Craig and he put the finished prototype in his van and drove it out to Nutley from Rantoul. When he arrived October 31, I informed Thornton, and the word traveled through the office. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Craig remembers: The bike and I waited in the BSA service room. Several hours went by as various BSA staff walked by. Typical comments were, "sure is orange" or, "never seen anything like that before." The fact is that nobody had seen anything like this and they really did not know what to make of it. Finally, Mr. Thornton walked in and there was an audible gasp, then he blurted out, "My God it’s a Bloody phallus! Wrap it up and send it England!" And with that, everyone laughed and clapped and began to give me compliments. The boss had told them it was okay. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don adds: No doubt you are right. I do not recall the delay, but it was probably because Thornton and I were having a small battle right in the middle of it. Thornton thought he had caught me with my hand in the pot and that I had absconded with corporate funds to fund the styling project! Craig recalls: In the next hour the bike was bubble-wrapped to be air freighted to England, and I returned to Rantoul, unpaid. I understood that I wouldn’t get paid unless it actually got made, but it sure sounded to me like it was going to be made. Only now, 35 years later, do I begin to understand the peculiar reception I was given at Nutley. There was a battle going on in the other room and Don was about to loose any ability to see his project through. How was I to know? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||