| Chapter Two: The New Triples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Following my appointment with BSA, my first trip to the UK was early in 1969 to view the BSA and Triumph triples that had been developed by Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele. I remember those present included my boss Lionel Jofeh, the chairman Eric Turner, Bert Hopwood, Doug Hele, and others from the UK. On the American side, there was Earl Miller of Triumph Corporation of Towson Maryland, Pete Colman of BSA & Triumph West in Duarte Californai, and myself, representing BSA, Inc. of Nutley New Jersey. Various subjects were discussed, including a review of a new model being designed by Edward Turner as part of his retirement program. It was never produced. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New 1969 BSA Rocket 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don continues: In many ways, the new triples were impressive to me, but they were also disappointing because they were still pushrod models with nothing very new, except that they were very fast. We knew by then that Honda was planning soon to introduce a big bike, probably a four. Another thing that was worrisome to me were the crankcases that were still split vertically. This meant we still faced the old problem related to British machines: oil leaking big-time. This was a warning signal that the Group hadn’t made the commitment to utilize pressure die castings necessary to go horizontal. Then there was the projected price, around $1,800, which caused me to grimace. But putting all of these things aside, there was one thing that really got to me: it was the rocket-shaped exhaust pipes, which reminded me of Bill Johnson’s 1959 Cadillac. I was very worried about such a design. Maybe it was not viewed that way by others, but it really got to me. Ted Hodgdon, who had shown me drawings of the silencers in 1968 before he retired, said that he had suggested a similar design and was proud of them and thought they were great. So, here I was, the new kid on the block, so I kept my mouth shut since the die had been cast. Interestingly, those silencers don’t really look that bad to me today. Maybe Ted was ahead of this time! Lionel Jofeh had instructed each of the American vice presidents to develop separate plans for launching the BSA and Triumph triples in the US market. In addition, my job was also to develop a national advertising program for the BSA brand. I didn’t mind; it was fun . . .so far. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

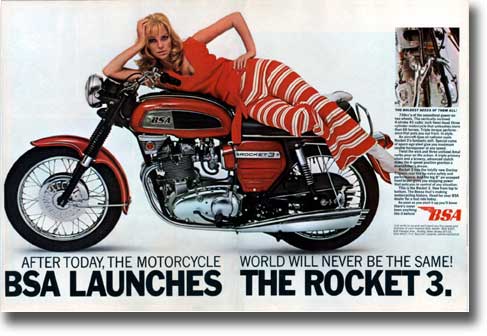

| Craig asks: Who did those girl ads? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don answers: I worked with a very creative guy by the name of Rick McBride from California to do the BSA ads. McBride had done work for Pete Colman. But, when Thornton came I was forced to hire a national ad firm in New York to handle all of the company’s adverting. It was the new agency that came up with the girly ads. It was a bad experience, but the photo shoots were fun and I tried to keep an open mind. It was my last assignment on behalf of BSA marketing, having been reassigned as vice president of national BSA sales. Thornton wanted his people to handle advertising and promotion, he knew I was on my way out, but he didn’t know that I also knew the end was near as a matter of personal choice. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

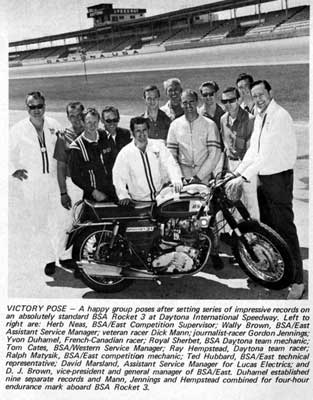

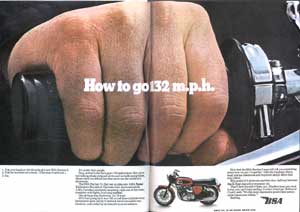

| Don again: To kick off the BSA campaign, I got an agreement from AMA president, Bill Berry, to officiate record attempts with the Rocket 3 at the Daytona Speedway. We leased the Speedway April 2 through 5, 1969, and hired Dick Mann, Yvone Duhamel, and Ray Hempstead for long-distance speed record attempts. These attempts were being made because our service manager, Herb Nease, told me he thought the new bike could go as fast as 130 mph if it was set up carefully to exact factory specifications. That got my attention because I respected Herb's opinion on such matters. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There is Don at the far right. Article courtesy "Motorcyclist" magazine, June 1969 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As it turned out, the attempts were highly successful, with a lap certified speed of 131.790 mph for the 2.5 mile oval, set by Yvon. Numerous other distance and speed records were also set, like 124.141 for 200 miles. Nobody else was close and these speeds until Kawasaki’s Z1 surpassed them at Daytona in 1972, but only by a relatively small margin. However, the Kawasaki records were approved by the FIM, which certified them as world records. Our BSA records were certified at the 1969 AMA Competition Congress as being set by standard production motorcycles. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The four bikes used to set the records were certified by the AMA as being absolutely to factory specifications, except we used K81 Dunlop tires front and rear. The front ribbed tire that came standard would not have endured the heat of high speeds on that track in April. Also, we replaced the standard handlebars with shorter ones, and the front fender was removed because it didn’t allow enough clearance for the K81 tire. That was it, and the project was a big success, as reported by Gordon Jennings in the July 1969 Cycle Magazine. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It didn’t save the Rocket 3 in the market, but it did cause the market to believe that the BSA version was faster than the Triumph version. It did look faster, having cylinders that were slanted forward. Whether the Rocket 3’s were really faster than the Triumph Tridents is another question. Sales of the Rocket 3’s in the first year were better than those of Triumph, but only just exceeded 1,800 units. |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

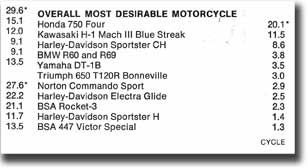

| Survey from August, 1969 Cycle Magazine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The speed and endurance records were achieved at a minimum of cost, but aside from the initial magazine publicity, Mr. Thornton later ignored them in favor of his successful bid to win at Daytona, at a huge cost. He could have used both events to prove how fast and durable the triples were, but he chose not to. I couldn’t help but believe that his decision was related to the fact that the speed records were my idea -- not his -- for introducing the Rocket 3 in the US market. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Don continues: While returning home from England early in 1969 after seeing the new triples, all I could think of was the bulky appearance of the BSA Rocket 3, those ugly exhaust pipes, and the projected high price. I was certain we were in for a tough time in the market place, especially if the inside information about Honda’s new bike was true. Today I often wonder whether I was right about those rocket style silencers. But it wasn’t just the silencers. I thought the triples looked too bulky and were not especially exciting in appearance. What mattered though was that I believed they were ugly, and this prompted me to take the next step. I gave a lot of thought to the styling of the Rocket 3. I knew nothing could be done and after all, it wasn’t my job to suggest styling changes, especially when the job was already done. I had to wonder what influence, if any, was brought to bear by my American colleagues on the styling of these new bikes before I came back on board. But what would I do if I could do anything at all? Over dinner on the return flight (first class yet), I began to think of my first bike and what had drawn me to it in the first place. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||